From Shahs To The CIA: The History Of Western Intervention In Iran

By Tyler Durden – Zero Hedge

Part 1

“Once you understand what people want, you can’t hate them anymore. You can fear them, but you can’t hate them, because you can find the same desires in your own heart” – concluded Andrew Wiggins in the novel Speaker for the Dead. When Americans hear the word Iran, many have a sort of knee-jerk visceral reaction. The very mention of the word conjures up frightful images of be-turbaned bearded imams leading mobs of Kalashnikov-carrying Muslim men and women whose faces are grotesquely contorted by intense anger as they enthusiastically wave banners bearing squiggly lines, no doubt saying, “Death to America”.

Such specters are no frightful flights of fantasy, but reflect a real time and place in Iranian history. The year was 1979 and the place was Tehran. But the Islamic Revolution and subsequent American embassy hostage crisis which shocked the world, catching the West completely off guard, did not materialize in a vacuum. The chaotic domino effect which would lead modern Iran into the hands of the Ayatollahs was set off from the moment the CIA intervened with its 1953 coup d’état in Tehran, which became known as ‘Operation Ajax’. But Western intervention in Iran’s affairs actually started many decades prior even to the CIA’s well-known covert operation with the establishment of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, or today’s British Petroleum (BP). After this, the 20th century witnessed a series of external interventions in Iran – a pattern which could potentially be continued now at the beginning of the 21st century as officials in the US and Israeli governments are now calling for action in support of protesters.

However, few officials and pundits in the West understand or care to know the tragic and fascinating history of Iran and Western interventionism there, even while feigning to speak on behalf of “the Iranian people”. To understand modern Iran and the chaotic events leading to the Islamic revolution of 1979, we have to begin with ancient history to gain a sense of Iranians’ self-understanding of their national heritage and identity, and then launch into the 20th century Iranian identity crisis brought about by foreign domination.

Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC, later called the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, and future British Petroleum/BP).

Belief in “Persian Exceptionalism” and Revolution

Iranian historian and professor at Tehran University, Sadegh Zibakalam, once defined the idea of “Iranian exceptionalism” as the dominant cultural narrative of modern Iran. Zibakalam explained this as “One of the strange features of 20th century Iranian leaders has been a tendency to perceive themselves, their government, and Iran as serious challengers to the present world order. Given the fact that the present world order is very much a Western dominated system, the Iranian leaders’ historic “crusade” has been broadly anti-Western. Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi as well as his successors have perceived their respective regime as offering the world a different system of leadership – one that is far superior to that of the West in many respects. Thus, Iranian “exceptionalism” rests on two main pillars: the negation of the present world order and the belief in the inherent superiority of Iranian civilization.”

This self-perception arises from the Iranian people being descendants of well-known historical rulers and an ancient people that civilized the desert of what was known to the rest of the world as Persia, and to us in our day Iran. The ruins of Persepolis hearken back several millennia to the days of the great Persian kings Cyrus, Xerxes, and Darius who in the magnificent Hall of Audience received the tributes of the various and sundry nations they conquered: the Elamites, Arachosians, Armenians, Ethiopians, Thracians, Ionians, Arabs, Assyrians, and Indians. They constituted an empire in every sense of the word, dominating some of the richest lands from Greece in the Eastern Mediterranean through Turkey in Asia Minor, northward to Lebanon, Israel, Egypt and Libya and then to as far East as the Indus river, engulfing the Caucasus along the way.

In so doing, they spread their knowledge of science, poetry, painting, architecture, and their Zoroastrian faith to the ends of the world. This faith ingrained in them the idea that it is the responsibility of everyone, rich and poor, young and old, to strive to attain and establish justice here in this world in much the same way that the Hebrews sought it through their Torah and the Buddhists through their Tao. The Persians were among those first great civilizations that turned men’s faces to the heavens and the stars challenging them to find meaning and purpose in a world replete with suffering and misery and to prepare their hearts, minds, and souls for the judgement that awaited them upon departing this life. Rulers, great and powerful though they be, were not exempt from this the common lot of man and thus were expected to rule justly guided by the light of their revealed religion. When they failed to do so, their subjects had the right to rise up and overthrow them. In this they were not exceptional. This is pattern that repeated itself time and time again through the long history of the Persians.

Birth of Shi’ism and Its ‘Underdog’ Identity

These conceptions of justice and of the duties of rulers remained a constant in the lives of the Persians, even after Darius and his empire fell and was absorbed by Alexander the Great in his empire in 334 BC. By assimilating and reshaping the culture of their conquers to fit their Zoroastrian faith, they continued to flourish, so much so that by the third century AD they had gained enough strength to lay siege to and conquer Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria, only to be repelled by the Byzantines at the walls of Constantinople in 626 AD. The death blow, however, came not at the hands of the Byzantine Christians, but by the invading Arabs who in the name of their leader and prophet, Mohammed, devastatingly defeated the morally impoverished Sasanian rulers, thus marking the end of the pre-Islamic dynasties in Persia.

Having been forcibly converted, the Persians set out to assimilate and reshape Islam, in much the same way they had done with the Greeks almost 1,000 years earlier, the result of which was a form of Islam different from the one their conquers had intended for them to accept, much to their consternation. Out of the martyrdoms of Ali and Hussein, relatives of Mohammed and rightful heirs to the caliphate, so they believed, was born Shia Islam. Thus, to their beliefs of justice and righteousness, were added the desire to cling dearly to those beliefs even to the point of death.

Corrupt Shahs Sell Out to Western Imperial Powers

For the next eight centuries the Persians endured, survived, and prospered even against the backdrop of the brutal rampages of the Seljuk Turks and the savage invasions of Genghis Khan’s hordes. Throughout those years, Iranians made great strides in music, poetry, architecture, and philosophy by sending their most learned to the centers of learning throughout Europe where they discovered Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Archimedes, and Ptolemy. In 1501 the militant Shiite, Ismail ushered in the fruitful, albeit repressive, Safavid dynasty that lasted until 1722, when Abbas Shah, the greatest and last of the Safavid kings died. Abas Shah was a great builder of roads and cities, and an indefatigable promoter or industry and trades throughout his empire.

In the chaos that followed his death, Iran experienced foreign invasions and violent internal struggles for power for the next 75 years. By the end of the century, the Qajar’s, led by Agha Muhammad Khan, wrested power away from the other competing factions and once again united the country. The Qajars were weak and greedy monarchs who were all too ready to hand over their country’s riches to the country, usually Britain or Russia, that had the deepest pockets with little regard for the well-being of their subjects. These corrupt rulers, more than any other internal factor, set the stage for the violent struggle the Iranians waged for freedom, democracy, and national sovereignty throughout the first half of the 20th century.

Nasser ud-Din Shah was one the first of the Qajar monarchs that the Russians and British intimidated, flattered, and bought. By 1872, ud-Din had virtually depleted the money he had stolen from his subjects through oppressive taxation and illegal seizures of property, so much so, that he could no longer afford his decadent and luxurious life style. To raise cash quickly, that year, Nasser ud-Din made a secret deal with the British through Baron Julius de Curzon whereby, for a paltry sum, the British were granted the exclusive right to operate and manage Iran’s vast irrigation system, mine its minerals, lay its railroads, manage its banks, and print its money. With unimaginable glee, Lord Curzon wrote that his deal with Iran was “the most complete and extraordinary surrender of the entire industrial resources of a kingdom into foreign hands that has probably ever been dreamt of, much less accomplished in history.” The concession had the predictable outcome of outraging common Iranians.

Britain’s Thirst for Persian Resources

In 1891 the Shah found himself strapped for cash once again. This time he decided to sell his country’s tobacco industry to the British Tobacco Corporation (BTC) for a mere £15,000. In so doing he stole from the Iranian his birthright to cultivate his native soil and enjoy the fruits of his labor thereby enriching his family, community, and country. There was no debate or vote since, by the rights of kings, he had the divinely ordained authority to dispose of his property, which is how he saw Iran, as he saw fit without consultation or even taking into consideration the effects such concessions would have on his people. Such actions only served to awaken the Iranians to the gross injustice of their political system and the necessity to replace it with one that existed to benefit all Iranians, not just the ruling class.

Meanwhile, the budding nationalistic spirit of neighboring and European countries, found its way into Iran through its educated class that readily consumed newspapers and monographs of the subversive type. These new and strange ideas challenged the belief in the absolute authority of the shah and revived once again the ancient Zoroastrian and Shia belief that rulers must be just and once they veer from that path, their subjects have the right and duty to remove them. Through this cross pollination of ideas the Iranians joined the growing chorus of nations that rejected despotism and authoritarianism and demanded from their rulers greater control over their individual lives as well as control of their country and its resources through the democratic process or face violent revolution, such as those revolutions carried out by the French and the Americans before them.

Iran’s first real taste of nationalism and came shortly after the tobacco concession. A national boycott of tobacco was called to force the shah to renegotiate with the British Tobacco Corporation. The boycott was a success and the shah had no choice but to inform the British that his earlier concession was in effect cancelled. But to appease the ire of his wealthy masters, the shah agreed to saddle his Iranians subjects with crippling debt through the Imperial Bank of Persia, another British corporation. Thus, Iran lay once again prostrate and humiliated before their colonial lords. On May 1, 1896, after giving thanks for a his fifty year reign at a mosque in Tehran, the rotten tree that was Nasser ud-Din saw was violently hewn down by ultra-national pan-Islamists who saw the shah and his ilk as nothing more than “good-for-nothing aristocratic bastards and thugs, plaguing the lives of Muslims at large.”

Nasser’s successor, Muzzaffar al-Din Shah proved to be no better at being a just and faithful ruler than had his father. He inherited from his father the expensive and humiliating habit of taking out large loans from the Russians and British to finance his lavish tours through Europe all the while ignoring the cries of his subjects for reform and relief from the intolerable burden of food shortages, unemployment, and skyrocketing inflation. With those funds exhausted, Muzzaffar turned to his father’s practice of selling his country’s patrimony to finance his expensive tastes. In 1901 the infamous British oil tycoon William Knox D’Arcy gave Muzzaffar a miserable £50,000 and a promise of 16 percent in royalties from annual profits. In return, the Shah gave him the exclusive rights for 60 years to do what he wanted to with the sea of oil that flowed beneath the Iranian sand. Like his father before him, he managed Iranian resources with little regard for his subjects whose livelihoods were dependent on those resources and with an eye to enriching himself. He stole from his own people and sold what was not his to sell.

Prelude to a Coup: Enter Future Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh

The Iranians, themselves, were keenly aware of this grave injustice and at the end of 1905, they took to the streets to protest the rise in food prices – demonstrations which often unraveled into riots and clashes with military forces. They demanded that the Shah listen to the voices of his people and establish a form of government that was governed by a constitution and that would allow their voices to be heard and obeyed. In the words of the revolutionaries they demanded “national consultative assembly to insure that the law is executed equally in all parts of Iran, so that there can be no difference between high and low, and all may obtain redress of their grievances”. These riots forced Muzaffar ud-Din to do what no other Iranian monarch had heretofore done and on the fifth of August 1906, by royal decree establish a parliament, or majles, thus laying the foundation for a constitutional monarchy. Among those young reformers that pressed their case for a constitution was the young Mohammad Mosaddegh, the man who would make Iranian nationalism his life’s work and obsession and which put him on a collision course with two of the world’s superpowers some 40 years later.

The country’s first parliamentary elections were held in the fall of 1906, in which only healthy “desirable” males were allowed to vote. The first majles held its maiden session in October of 1906. Their first order of business was to draft a constitution, but rather than trying to reinvent the wheel, the majles modeled their own constitution after the Belgium constitution which by the standards of the day was considered the most progressive in Europe. Right away the majles began to butt heads with the new Shah, Muhammad-Ali by denying him foreign loans for his personal use. This was just the first of many clashes to come between the majles and the Shah.

By 1907 the country was engulfed in a civil war between the constitutional revolutionaries and those loyal to the Shah. The violence came to a head in June of 1908 when the Shah’s elite fighting unit overwhelmed the revolutionaries and utterly crushed them. Thus, after only two years Iran’s nascent constitutional democracy was snuffed out. Though never legally abolished, the majles after 1908 was seen by the Iranians as a sham assembly of handpicked “desirables” that rubberstamped the shah’s capricious decisions. Many of the revolutionaries were executed and those that survived fled to Europe, some to plan their return, others to forget the misery of their homeland. Among them was Mohammad Mosaddegh.

Britain Takes Control through the Anglo-Persian Oil Company

With the bothersome majles out of the way, Muhammad-Ali Shah could once again turn his attentions to raising money for his personal expenditures. He had to look no further than the deal his father made with D’Arcy in 1901. D’Arcy’s investment paid off in a big way when in 1908 the Burmah Oil Company, who bought D’Arcy’s lucrative rights, struck oil at Masjed Soleyman. One year later the company changed its name and became the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC, or later Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, and future British Petroleum).

About the same time Winston Churchill, then the First Lord Admiral of the Royal British Navy, finalized the process whereby oil replaced coal as the fuel that powered the vast British navy. With that, England’s need for oil sky rocketed. To meet the soaring demand for oil, that same year the British opened the Abadan in Iran refinery and in 1914, and to ensure that the oil economically found its way to its military, the British government bought 52.5 percent of the shares in APOC. This is one of the most ironic and hypocritical facts of the entire saga given that the British government had no qualms about nationalizing the oil industry in its own country, but were prepared to ignite war because Iran had made the same choice in the 1950’s.

“The Empire Must Go On”

Once Europe erupted in world war, the British dispatched their armed forced to refineries all over Iran in order to protect what they considered their property – Iranian oil. After the cessation of hostilities in 1919, the British bribed and intimidated the new regime of Ahmad Shah into accepting the terms of the much hated Anglo Persian Agreement which in all but name, made Iran a protectorate of the British Empire. No longer would the Iranians control their own army, transportation system, and communications network. It all passed under the control British occupiers and with it the last vestiges of Iranian sovereignty. This once again ignited the fervent nationalist spirit across Iran and new rounds of protests and opposition.

Even the U.S. president, Woodrow Wilson, disapproved of the agreement. But, true to their colonial and imperialist spirit, the British rebuffed such protestations and opposition by saying, “These people have got to be taught at whatever cost to them, that they cannot get on without us. I don’t at all mind their noses being rubbed in the dust.” The empire must go on.

Part 2

And go on it did, fueled by the black gold that flowed beneath the Iranian deserts. For the next thirty years, relations between the Iranians and the British revolved mainly around oil. The British deposed and installed new kings, and prime ministers and members of Iranian parliament were bought off to help ensure the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (by that time renamed the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, or AIOC) had a free hand in the exploration, refining, and exportation of Iranian oil. For that was indeed the bottom line for the British – the Iranian venture was extremely profitable for them.

Churchill’s Dream Prize

Indeed, for Churchill, it was, “a prize from fairyland beyond our wildest dreams.” When they started in 1913, the British were extracting only 5,000 barrels of oils per day, and by 1950 they were extracting 664,000 per day. Had the wealth from the oil been humanely shared with the Iranian people, the Iranians themselves likely would have seen such growth as part of a mutually beneficial relationship and endeared them to the English. However, the long list of grievances hardened the hearts of the average Iranians and confirmed what they had long known: Britain was an empire whose only objective was preserving its interests, whatever the costs to Iranians, notwithstanding British protestations to the contrary.

It is easy enough, however, to see why the British were prepared to go to the extreme to protect their direct access to cheap Iranian oil. Iranian oil was vital, not only to the Royal Navy, but to the entire economy of Great Britain and their way of life. It fueled their industries and growing automobile culture. The AIOC was a vast company with seemingly limitless profits and resources, yet it sought still more from the Iranians. From the British perspective the situation seemed like good capitalism, but from the perspective of the average Iranian, their British “benefactors” were greedy imperialists who were prepared to suck Iran dry.

The majles (Iranian parliament, which held its first session in 1906), weakened though it was, gradually regained strength throughout the late 20s, 30s, and 40s, mainly from the rise of anti-British and anti-Shah sentiment coursing through the nation. The majles forced the Shah and the oil companies to come to the negotiating table time and an again seeking just compensation and to redress the wrongs commited by the oil company. The list of grievances was indeed long. At the top was the irregular bookkeeping that systematically deprived them of their contractual rights to royalties. Instead of calculating the Iranian 20 percent before taxes, the British calculated the Iranians their portion after they had already sent huge sums to the British treasury, which meant, the Iranians received much smaller royalties.

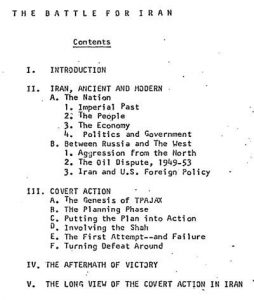

Recently declassified documents like the above ‘The Battle for Iran, 1953’ (Contents page: view more here) tell the CIA’s secret internal history of the 1953 coup. It was only in 2013 that the CIA formally acknowledged its role in bringing down the Mossadegh government after the agency was forced to declassify and publish secret documents related to Operation Ajax, (and first disclosed by The New York Times’ James Risen) and to this day most Americans are unaware that it happened.

Additionally, in 1943 the British stubbornly, and in the eyes of the Iranians, greedily, refused to renegotiate their contract to reflect the growing global trend to fairer and more equal contracts. Venezuela signed a 50/50 deal with the foreign companies refining its oil; Aramco, an American oil company, signed a 50/50 deal with Kuwait and Saudi Arabia; and Mexico took advantage of the chaos of WWII and did the unthinkable and completely nationalized American and British oil companies. The Iranians felt it was time that the British dealt justly and fairly with them as well.

Not only did the British fail to fairly compensate the Iranians for their oil, they only paid them in sterling, effectively barring them from buying from other countries and forcing them to buy from the British. They also secretly conducted geological explorations without the consent of the Iranian government, much less the Iranian people. These explorations, plus the building of pipelines, often laid waist to forests, water sources, and other natural resources resulting in massive ecological disasters. To add insult to injury, the British often imported labor from neighboring countries, rather then giving the Iranians the opportunity to work and make a living, much less take leading and managerial positions, in their nation’s most vital industry. Squalid company housing, hospitals, and working conditions coupled with firings and military action against unions were also on the Iranians’ long list of grievances against the oil company.

The Shah meets the CIA

Beginning in the mid-40s tensions between Iranian workers and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company came to a critical impasse. In July of 1945 7,500 AIOC workers led an unsuccessful strike demanding equal pay, decent housing, and paid Fridays. They took to the streets again in May of 1946 with similarly disappointing results. It wasn’t until May of 1946 when 50,000 workers organized the greatest strike in Iranian history that the AIOC realized it had no way forward unless it made some concessions, though they probably came too little, too late to turn the tide of anti-imperialism/colonialism felt by the vast majority of Iranians.

Negotiations between the majles and the AIOC stalled and stagnated for the next 5 years. With each passing year, the bitterness and resentment grew among the Iranian people who were tired of decades of what they felt was theft and national humiliation at the hands of British colonialists. The thirty-year-old monarch, Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi did little to assist his countrymen in redressing the wrongs of the British. In fact, at the height of the conflict between the majles and the AIOC, the young Shah abandoned Iran and set off on an American expedition where he mingled with the most wealthy and powerful of America’s elites.

In November of 1949, at the invitation of Allen Dulles, the future head of CIA introduced Mohammed Reza Shah to the members of the newly formed Overseas Consultants Inc. Mohammed Reza singlehandedly committed his country to paying the OCI an astonishing $650 million to complete a massive development project in Iran. The deal was not well received at home since the majles had not approved of it or been consulted. It did nothing more than stoke the flames of the revolution that much more. The final straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back came in March of 1951.

Nationalizing Oil under Mohammed Mossadegh

Having failed to reach a just and equitable agreement with the AIOC, the majles felt it had no other recourse than to take the course of action that the Mexicans had taken a decade before and nationalize their oil industry. In March of 1951 the majles voted to take that fateful step and a few days later they elected the charismatic nationalist, Mohammed Mossadegh to the office of prime minister. One of the first casualties of the Mossadegh-led majles was the $650 million OCI deal, an act Allen Dulles would remember with bitter resentment. Mossadegh believed with every ounce of his body that the Iranian oil fundamentally belonged to the Iranians. Prior agreements with corrupt kings could not and should not be honored since they were made without the knowledge or consent of the people through their elected officials.

Meanwhile the British took no notice of these legitimate claims and by June British warships menaced the Iranian coast and plans had been drawn involving seventy thousand troops invading Iran to seize what it claimed were British oil fields. The American ambassador, Henry Grady, warned the Truman administration that the British intransigence and belligerence was utter folly and could easily trigger World War III. Truman, in no uncertain terms, informed Churchill that the United States would not agree to or support the overthrow of another democratically elected government.

Even after nationalization, the Iranians sought to compensate the British by sharing 25 percent of the net profits of the oil operation. It also guaranteed that the British citizens who stayed and worked for the newly formed Iranian Oil Company would be welcome to stay. It would also continue to sell the oil exactly as the British had done making sure not to disrupt the long-established system of controls. The British were not content with these compromises and stubbornly insisted on a return to the status quo where they, and they alone owned, managed, and controlled every aspect of the Iranian oil industry. “We English have had hundreds of years of experience on how to treat the natives. Socialism is all right back home, but out here you have to be the master” boasted one British minister.

British Dirty Tricks, Eisenhower, and the Dulles Brothers

Over the next year the British contemplated every trick they had learned in their long years of empire building: sabotage, assassination, bribery, and even a full-on military invasion. But Truman’s opposition to regime change limited their options. So in the meantime, they settled on imposing a crippling blockade of Iranian ports so that no country could buy oil from the Iranians. Any tankers caught trying to slip through would be detained.

The British also took their case to the International Court of Justice in the hopes of getting the international community to bolster its position only to be told that the ICJ had no jurisdiction in the case since it involved agreements between Iran and a private company. They took their case once again to the UN in New York in the fall of 1952 but met a brick wall there as well. Mohammed Mossadegh was present and he spoke forcefully and eloquently about the plight of the Iranians and about the history of the AIOC’s predations. His speech was well received especially by those leaders who themselves had been brought to power on the waves of nationalism in Asia, Africa, and South America.

Having exhausted all resources, the British resolved to covertly overthrow Mohammed Mossadegh, even though 95-98 percent of the population of Iran time and time again favored him as their one true leader in elections and referendums. They could not count on the Truman administration for support, so they bided their time until after the 1952 elections which could bring someone that was more to their way of thinking or could be brought around to it. They found such a men in Dwight Eisenhower, in his Secretary of State, Foster Dulles, and in Allen Dulles, head of the CIA.

A Deep State Purge

The British argument for overthrow rested on the necessity to regain the control of the oil industry away from the Iranians. However, that argument alone would not be enough to win over Eisenhower and Dulles. All three men were ardent anti-communist and the British used that to their advantage painting Mossadegh as a communist at worst and at best, a weak leader whose government could easily fall which could lead to a Soviet takeover of Iran. These were all the reasons and proofs Eisenhower and Dulles needed. Without consulting experts or career diplomats on Iranian affairs they forged ahead with their plan to help the British topple Mossadegh.

They even went so far as to dismiss any who disagreed with them. One such unfortunate was none other than the chief of the CIA field office in Tehran, Roger Goiran. If anybody knew what the realities on the ground were, it was he. Having learned of the plot he was repulsed by the idea and thought that regime overthrow in the cause of a preemptive strike of sorts in order to prevent the Soviets from theoretically moving in was too dramatic a move. His objection was noted after which he was quickly relieved of his duties and replaced by Kermit Roosevelt, one of the conspirators.

Ultimately, seasoned intelligence veteran Goiran disagreed with and was subsequently purged by the ‘deep state‘ as Stephen Kinzer’s book All the Shah’s Men (John Wiley and Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, 2003, pg. 164) explains:

Goiran had built a formidable intelligence network, known by the code name Bedamn, that was engaged in propaganda activities aimed at blackening the image of the Soviet Union in Iran. It also stood ready to launch a nationwide campaign of subversion and sabotage in case of a communist coup. The Bedamn network consisted of more than one hundred agents and had an annual budget of $1 million–quite considerable, in light of the fact that the CIA’s total worldwide budget for covert operations was just $82 million. Now Goiran was being asked to use his network in a coup against Mossadegh. He believed that this would be a great mistake and warned that if the coup was carried out, Iranians would forever view the United States as a supporter of what he called “Anglo-French colonialism.” His opposition was so resolute that Allen Dulles had to remove him from his post.

This was new and unchartered territory for the United States in Iran or anywhere. Up to then, most Iranians had a positive view of America and look up to Americans because of their own revolutionary history, constitution, form of government, and insistence on the rule of law.

Operation Ajax Launched with False Flag subversion

The Iranians viewed the Americans as allies and friends. By undertaking regime change, the Americans risked losing the goodwill of the Iranians and earning their much-deserved scorn. Nevertheless, Kermit Roosevelt took the reins of the operation and plotted his coup for several months. Once he was given the green light by the Dulles brothers and President Eisenhower, Roosevelt set his plan in motion. In late July of 1953 he crossed over into Iran under an assumed name and headed directly to Tehran to meet up with the valuable Iranian, British, and American assets. They immediately set out to subvert the Mossadegh government by paying off street gangs, corrupt mullas, and radio stations to create entirely fabricated anti-Mossadegh protests. They also bribed members of the majles to support a vote of no confidence. Mossadegh caught on to the plot and immediately dissolved the assembly, denying the conspirators any chance at a quasi-legal way of deposing him.

Persian soldiers chase rioters during CIA-orchestrated civil unrest in Tehran, August 1953. Archive photo via Foreign Policy magazine.

Once plan A crumbled, Roosevelt put plan B into action which called for the Shah himself to sign royal decrees dismissing Mossadegh from office and appointing General Fazlollah Zahedi as his new prime minister. The Shah demurred, going so far as running away to the Caspian Sea. In the end, Roosevelt caught up with him and convinced him to sign.

On the night of August 14, 1953, Roosevelt sent Colonel Nassiri and a contingency of soldiers to Mossadegh’s house. Their task was to present the royal decrees to Mossadegh and take him into custody. To their surprise, Mossadegh had been tipped off about the plot and had in the shadows a contingency of officers of his own ready to take Col. Nassiri and his men into custody. The following morning, Radio Tehran announced that the government had successfully foiled the plot by the Shah and foreign elements to overthrow the government.

Having heard the news, Roosevelt’s CIA superiors urged him to give up the plot and return home. However, not being one to back down, Roosevelt forged ahead. For the next 4 days, through his Iranians assets Roosevelt hired more street gangs to simultaneously put on pro and anti Mossedegh demonstrations. The demonstrations had the desired effect of plunging Tehran into an abyss of violence and lawlessness.

Coup d’etat

On August 19th the violence reached its climax paving the way for the final part of Roosevelt’s plan: a full-on military coup. At noon the military and police officers Roosevelt had bribed, stormed and took control of the foreign ministry, the central police station, the headquarters of the army’s general staff, and laid siege to Mossadegh’s house. Mossadegh narrowly managed to escape, but turned himself in the following day to General Fazlollah Zahedi, not wanting to be the cause of further bloodshed. Zahedi played a large role in the coup in cooperation with the CIA and Britain’s MI6 and would go on to replace Mossadegh as prime minister.

The fall of Mossadegh, on August 20th, 1953 also marked the end of Iran’s long and painful march to true and complete democracy and national sovereignty. It also marked the beginning of a 26 year reign of corruption and oppression in which Mohammed Reza Shah, quickly returned to power by the 1953 coup d’état, brutally stamped out the pro-democratic reforms of the majles, violently put down any opposition, as well as what arguably angered the Iranians the most: the Shah returned the oil industry back to Western corporations, once again depriving the citizenry of the wealth that rightly belonged to them.

Iranians, unlike many average Americans who are not taught this history in school, have always known that America was involved in the overthrow of their democratically elected government and have thus hated the US government ever since. This hatred was seen most vividly in 1979 Islamic Revolution when 52 embassy staff in Tehran were held hostage for 444 days.

It was only in 2013 that the CIA formally acknowledged its role in bringing down the Mossadegh government after the agency was forced to declassify and publish secret documents related to Operation Ajax, (and first disclosed by The New York Times’ James Risen) and to this day most Americans are unaware that it happened. Yet it is essential to understanding the historical domino effect that American and British interventionism played in bringing the US and Iran to their modern period marked by decades of animosity and enduring mutual distrust.